Negotiated Curriculum: The Questions Come from the Kids

This week's contributor is Lindsey Halman. She has taught middle school in Vermont for the past fourteen years and is currently teaching at Essex Middle School where she is a co-founder of The Edge Academy team. The Edge Academy integrates education for sustainability, as well as the arts, into all aspects of the team and curriculum.

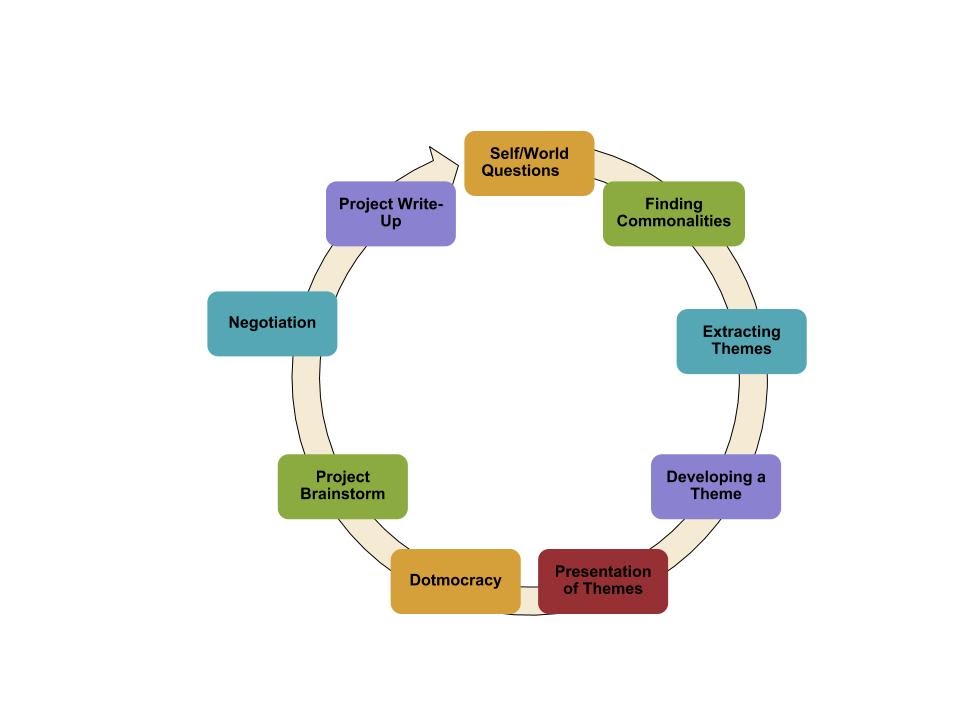

The Edge Academy has adapted a model we call “Negotiated Curriculum” from the work of James Beane. This model begins with the learners developing questions and concerns they have about themselves and the world. The strength of this collaborative curriculum model is in its coherence and permeability. It is “coherent” through its holistic approach to content areas by integrating subjects, rather than approaching them as a set of fragmented, unrelated topics. In this way, it reflects the natural relationship between different disciplines of knowledge. It is “permeable” as it is based on learners’ own questions about themselves and about the world, and on the facilitators’ understandings of questions the world poses to learners. This permeability provides room for learner choice and voice. Learners’ questions are rich and from these questions, learners develop their ideas for their project work.

Once our learners have developed their questions and/or concerns about themselves and the world, they work in small groups to find commonalities amongst their questions. During the process of sharing questions, this helps to establish relationships as well as trust amongst their team members. As they listen to one another’s questions, they are carefully considering their own and if there are commonalities.

Once they have discovered the commonalities amongst their self and world questions, they begin the process of extracting themes. This is a challenging, process for young adolescents that involves critical thinking skills and intense collaboration. In this process they are asked to connect their common questions to big ideas, such as change, future, conflict, creativity, etc. As facilitators, we can model and guide our learners through this process, yet the outcomes are completely up to their questions and the collaboration that they experience in their groups/

Each group then agrees upon one theme to develop. This process involves creating a systems web to show the connections between the theme and the different aspects of curriculum on our team. This is the only time, throughout the year, that we ask the learners to think about their theme in connection to discrete subject matter (humanities, math and science). We find this to be an important part of the process so that they can demonstrate their understanding of how this theme can be integrated into all of their learning. We also ask them to think about how it connects to: sustainability, the arts, technology and our community. When thinking about the community, school, town, state and global, we ask the learners to also think about who in the community could help advance their project work.

After our theme posters are created, each group creates a short presentation of their theme for the team. This allows the students to not only practice their presentation skills in front of a large audience, but it provides them with an opportunity to articulate their hopes and dreams for our project work. Posters are then displayed in a “gallery” and our learners are expected to take the next day to ponder the themes and think about the theme that best aligns with their interests and passions.

We then use a process called “Dotmocracy” to determine our overarching theme for the year. Each member of the team (learners and facilitators) receives two colored dots to use as votes for the theme they think will most align with their interests and passions. This process not only models a democratic process, but it honors each individual's voice on our team by providing them with the opportunity to make their own choices in regards to our pathway for the year.

Once a theme is selected, learners spend time thinking about the theme. For example, when we had the Creativity: If you can think it, you can make it!, learners spent a couple of weeks thinking about the word creativity and exploring how they use creativity in their own lives. As facilitators we provide them with articles, videos, experts and activities to develop a foundation for their project work. Small projects occur in order for the facilitators to “teach” the essential skills that will be needed for their year-long projects. This involves teaching how to research effectively, document learning and share their learning with others. During our Creativity theme, we had our learners research the one innovation/invention that they felt was the most important in human history. They then had to find evidence to back up their claim and create a short presentation to the team to convince them that their innovation/invention was the most important. From there, we had learners think about what creativity means to them and then using any medium they chose, they demonstrated what this word meant to them. We had learners create videos, felting, drawing, writing, building, etc., to demonstrate their creativity.

Once the foundation of the theme has been built, we provide learners with some space and time to think about what their project might look like for the year. This is the key component of the negotiation process. Once they have brainstormed their ideas for projects they submit them to the facilitators. My teammate and I then review their project proposals and think about groupings, topics, resources, etc. to make these projects possible.